Recently I saw someone spreading the folklore that the internet, which was initially computers at academic institutions sitting in rooms without any fortification, security or backup power, was designed from the start, to withstand a nuclear attack.

This is disputed by people who did the actual designing of the internet.

In texts that give Internet History a serious treatment, such as the 1996 “Where Wizards Stay Up Late - The Origin of the Internet” you can search the word “nuclear” and come up with passages like this:

Bob Taylor… was also on a personal mission to correct an inaccuracy of long standing. Rumors had persisted for years that the Arpanet had been built to protect national security in the face of a nuclear attack. It was a myth that had gone unchallenged long enough to become widely accepted as fact.

and

Lately, the mainstream press had picked up the grim myth of a nuclear survival scenario and had presented it as an established truth. When Time magazine committed the error, Taylor wrote a letter to the editor, but the magazine didn’t print it. The effort to set the record straight was like chasing the wind; Taylor was beginning to feel like a crank.

Here’s Vint Cerf, in July 2022 still trying to correct this folklore. Somehow this one got out of hand and the people who were there have been trying to politely correct it in vain for decades.

The problem is that surviving a nuclear war is such a more memorable story than wanting to try out the first massively parallel computer, the ILLIAC IV. The designer of the machine, Daniel Slotnick, was also a chief architect of the ARPANET which was built partially to get the computer to be online in order to justify the cost of building the computer. This way more scientists could use the expensive machine doing remote time-sharing.

See you glazed over that. I know it. Isn’t “bringing the mainframe to the battlefield” more sexy? That’s June 2022. That’s why these myths perpetuate.

The early internet looked nothing like the mountainside NORAD bunkers you see in movies. Unlocked offices in university buildings without any real security (network or physical), no connections to military communication centers, no military clearance required to use or work on, it doesn’t really make sense if your goal is “survive World War III”. That of course, doesn’t matter.

Let’s look at some early versions of the story to get a better understanding.

The first instance I was able to find of the misattribution is a both victim of how chronology works and slight journalistic error. The Aug 19, 1991 issue of Network World has a bio on someone who will be important in our story, Paul Baran. It’s a long passage. Feel free to read it. I summarized it here:

… questions were being asked regarding the U.S.’s ability to survive a pre-emptive nuclear attack with enough of its military capability intact … Baran and his Rand colleagues decided to keep the packet-switching research unclassified… After delays caused by political issues, the government commissioned a public net based on Baran’s research (my note: false). In 1969, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency completed the first packet switched net, dubbed ARPANET.

This is the correct timeline, but not the correct chain of events and it’s not the last time it will be made.

It’s a fairly buried reference, literally right near the end of the magazine, after the small back-of-the issue ads. The next appearance however, is quite a bit more prominant.

Probably the first to claim a bomb connection is “The Whole Internet User’s Guide & Catalog” from September 1992 by Ed Krol. This is one of those books that’s so succesful he comes back to pen two sequels. Amazon even sells a Japanese version. Here, in a very prominant place, near the beginning of the book, we get our story however, the word “nuclear” isn’t even used, instead it’s a generic “bomb attacks”:

It’s worth noting that this is an honest error of connecting a project that didn’t ever get approved (the bomb resiliant project by Paul Baran proposed to the Air Force) with the ARPA Network project (more on that later). Specifically this is referring to what Baran called “hot-potato routing” in 1964.

Without knowing the specific people involved in each project it is understandable to assume these are connected and that a later effort was a result of an earlier effort as opposed to an independent one.

The boring every day bomb gets an upgrade in what was at the time, a best-seller, the 1993 text, “The Internet Navigator” by Paul Gilster which, on page 14 says in an uncited passage:

The ARPANET was a network connecting university, military, and defense contractors; it was established to aid researchers in the process of sharing information, and not coincidentally to study how communications could be maintained in the event of nuclear attack.

Ladies and gentlemen, we’ve gone nuclear.

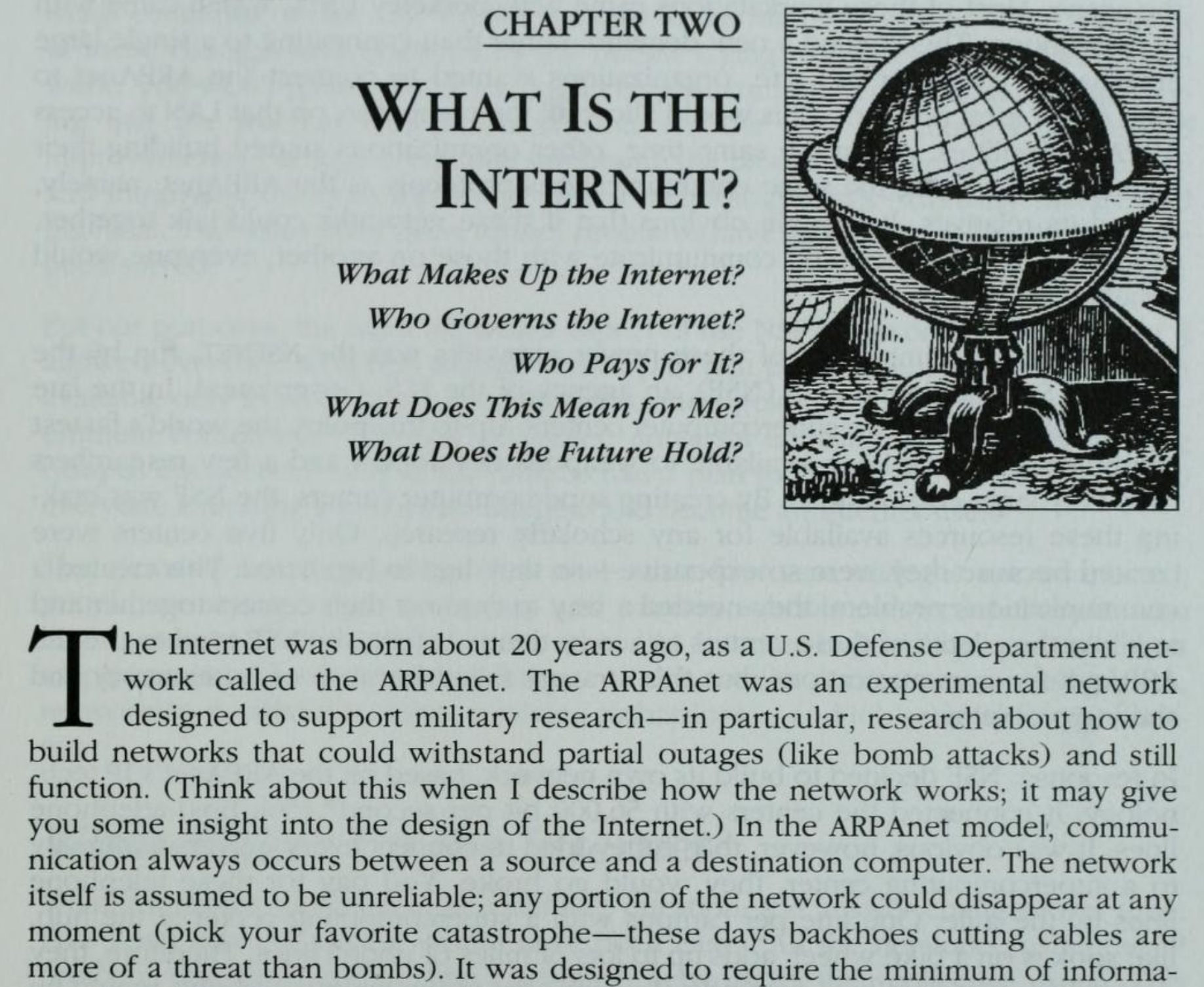

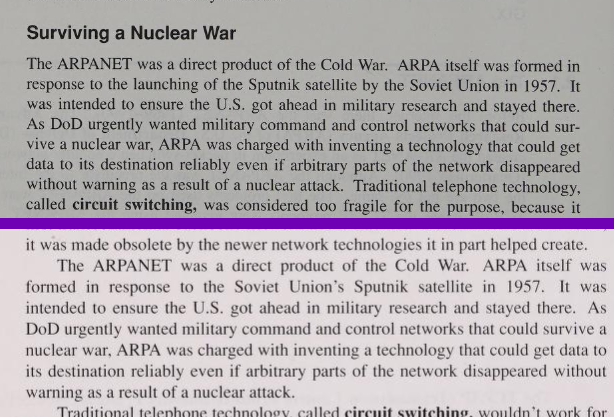

This connection gets repeated in texts such as 1994’s “The Internet connection: system connectivity and configuration” where the author, John Quarterman states without citation in a section titled “Surviving a Nuclear War” a very similar passage he stated in a 1993 text, “Practical Internetworking with TCP/IP and Unix”:

It’s worth noting that John Quarterman either apparently knew better or had his mind changed on this. In an earlier 1990 text by him, The Matrix: Computer Networks and Conferencing Systems Worldwide he used a citation and told a much more accurate history as follows:

In the beginning, ARPA…noticed that its contractors were tending to request the same resources (such as databases, powerful CPUs, and graphics facilities) and decided to develop a network among the contractors that would allow sharing such resources [Roberts 1974].

Why didn’t he just stick with that?

This “ARPAnet is one step removed from nuclear war planning” narrative was common in 1993 and 1994 texts, such as in “Japan’s Information Highway” from Nov 26, 1994, also uncited:

Spawned by a Pentagon doomsday scheme to keep US military computers operating in the event of a nuclear war, the Internet…

In all these claims the statement was ARPA was looking for a resilient network due to cold war politics with the risk of nuclear war playing somewhere in the background and the ARPANET came out of this dynamic.

As 1993 became 1994, we got perhaps the first claim of a direct causal connection from INSCOM (Army Intelligence & Security Command) in March 1994 on page 10:

…says University of Pennsylvania Telecommunications Professor David Farber, “that the Internet is actually a cold war relic, designed in the 1960s as a decentralized military communications system capable of surviving a nuclear attack. The Internet, which has grown explosively ever since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, has now proved its usefulness for emergency action in the civilian world.”

Here’s where we find the first instance of that phrase. David Farber is not a nobody. Designer of predecessor networks such as CSNET, NSFNet, and NREN, he’s a Bell Labs, SDS and Rand Corporation alumni. That last one, RAND, will be more important in our story.

From here on out, this became a common narrative repeated in many texts and just as often pushed back on.

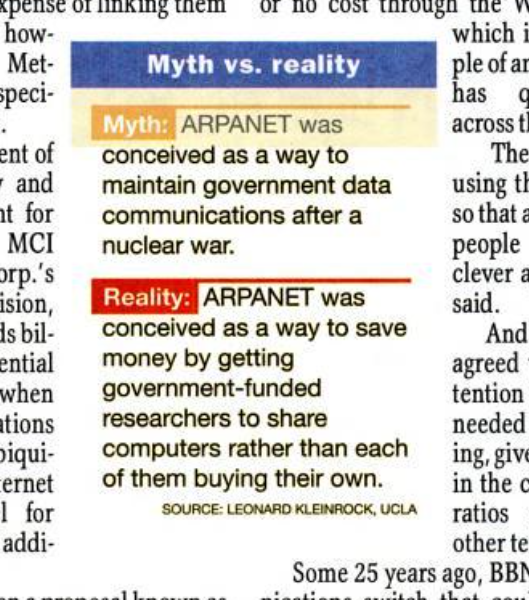

In Network World from Aug 22, 1994 they put a special “Myth vs. Reality” inset from Leonard Kleinrock to try to dislodge things

It was hopeless. Network World was the first source we found for spreading it to begin with.

It became so stuck that people started making logical inferences from it in academic textbooks such as “Global communications : opportunities for trade and aid.” from 1995, page 102:

…the desire for a computer network that would remain operational in the event that part of the network was destroyed by a nuclear explosion. The ARPAnet therefore had no central control.

You even get hybrid narratives that have both the fiction and the reality. Watch the narrative grow in the 1995 academic text, “Technology in the national interest”

war planners undertook and effort to ensure the survivability of America’s computing and communication capabilities in a nuclear first strike to preserve a credible U.S. retaliatory capability. From this initiative the first network, ARPAnet, was established, allowing geographically separated researchers to share computer resources.

After that it was off to the races, such as in this 1995 text, VRML browsing & building cyberspace : the definitive resource for VRML technology

This myth has serious sticking power and other than for the people who actually built the internet, nobody seems to have any desire to correct it.

Like any good conspiracy theory, there’s related truths that make the core message believable. The ARPANET project was by DARPA, which was under the Department of Defense. This organization was launched after Sputnik. The military had something called MILNET, it’s own split-off from the internet from 1983 which became NIRPNET.

In 1971 the command and control WWMCCS had an ARPANET like system using BBN IMPs. ALOHAnet did lead to PRNET and a packet-radio van which interacted with a satellite network, SATNET. Before that there was a trans-atlantic link, NORSAR connecting to seismic units in Norway to, among other things, enforce the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

There is some cold war connection, just like there is in much of computer technology from the era. The generalized statement that DARPA money funded Silicon Valley is true and it’s understandable how fuzzy memories and a bit less rigor can fuse connections.

Also there’s a conspiracy tendency when it comes to grim folklore. Perhaps people denying the nuclear war connection have a political agenda, they were misinformed or they are too scared to admit it. It has its own defense built in that permits people trying to correct the narrative to be dismissed as trying to push an opinion or occluded political agenda.

However, the documentation is voluminous and the people who were in the room have all given a consistent story about how it was to build a network for time-sharing of expensive computers and better collaboration.

There’s apparently too many general associations too long ago to dislodge the false narrative. People have a tendency to not be careful with chronologies and attribute events in a narrative structure that would require people time-travelling to be true.

To put this in perspective let’s use living recent memory. It would be like seeing a connection between say COVID-19 pandemic outcomes being related to political governance, that there was a 2012 Ebola outbreak and then claim the outcome of the Obama/Romney 2012 election was a direct consequence of the federal COVID-19 response.

That’s really the same dynamic. Events in the 1970s are being placed categorically adjacent to events in the 1960s and after the table is set, a narrative is drawn between them.

This wasn’t always the case.

Prior to 1991 there are no history of the Internet/ARPANET (and sometimes referred to as DARPANET in the mid-to-late 80s and “ARPA Network” prior to 1969) which speak of this supposed doomsday connection.

In April 1988 for instance, Infoworld says

The network was originally set up for universities and research organizations to exchange information efficiently

In “DARPA Technical Accomplishments”, from 1990, ARPANET isn’t listed in the Nuclear section but the “Information Processing” section. It documents the history in the “batch-processing” to “time-sharing” revolution framing. From section 20-1

After time sharing had been demonstrated and its impact began to be widespread in the mid 1960’s, the next logical step in this program was the linking of computers and terminals by communications networks, so that computer capabilities, programs and file resources could be accessed readily and shared remotely. The mainstream of ARPANET development involved individuals and institutions in the computer research communities which were supported by the growing ARPA IPTO program.

Even up through 1992 this persisted, such as in “DNS and BIND in a nutshell”:

The original goal of the ARPANET was to allow government contractors to share expensive or scarce computing resources. (time-sharing) From the beginning, however, users of the ARPANET also used the network for collaboration. This collaboration ranged from sharing files and software and exchanging electronic mail - to joint development and research using shared remote computers.

So where did this start? Why does David Farber differ from the narrative and where did people like Gilster and Quarterman get this idea?

Farber, Gilster and Quarterman were emailed individually and asked for clarity but as of Sep 27, 2022, none of them responded. I was unable to find a way to reach Ed Krol. Corrections can be sent here.

As I’ll cover in further articles in this series, there’s no expectation that an engineer be a historian or that accurate scholarship can be expected in the days before mass digitization especially in texts where the history isn’t a focus of the scholarship.

Also, the prevailing assumption is to look for mistakes before assuming malice. Not just because it’s more polite to do so but also because these statements are small buried passages in much larger, often dry technical works. There’s no evidence these authors are fabulists trying to tell compelling stories.

Well except for one.

In February of 1993, the science fiction author Bruce Sterling made perhaps the most compelling narrative fixture of what could be the source of the later folklore. This text was shared around USENET throughout 1993. USENET was in practice, social networking via the medium of email.

In it there’s a clean narrative line that’s drawn between Paul Baran and ARPAnet. It’s a long passage so some cutting was done

…the RAND Corporation, America’s foremost Cold War think-tank, faced a strange strategic problem. How could the US authorities successfully communicate after a nuclear war?

Postnuclear America would need a command-and-control network, linked from city to city, state to state, base to base. But no matter how thoroughly that network was armored or protected, its switches and wiring would always be vulnerable to the impact of atomic bombs. A nuclear attack would reduce any conceivable network to tatters. …

RAND mulled over this grim puzzle in deep military secrecy, and arrived at a daring solution. The RAND proposal (the brainchild of RAND staffer Paul Baran) was made public in 1964. In the first place, the network would have no central authority. Furthermore, it would be designed from the beginning to operate while in tatters. …

During the 60s, this intriguing concept of a decentralized, blastproof, packet-switching network was kicked around by RAND, MIT and UCLA. The National Physical Laboratory in Great Britain set up the first test network on these principles in 1968. Shortly afterward, the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency decided to fund a larger, more ambitious project in the USA. The nodes of the network were to be high-speed supercomputers (or what passed for supercomputers at the time). These were rare and valuable machines which were in real need of good solid networking, for the sake of national research-and-development projects.

Look how smooth that is. Only a professional story teller could pull it off. Such a subtle mistake.

To dig deeper on this we’ll refer back to the 1990 DARPA document.

From “DARPA Technical Accomplishments”, section 20-2 we find this:

Notable early contributions had been made by P. Baran and collaborators at RAND. Baran’s work in the early 1960’s outlined a distributed, survivable digital communications system for the Air Force, in which a data stream would be broken near the point of initiation into addressed subunits of less than two hundred bits, which would then be routed by “intelligent” nodes over multiple paths which could include satellites as well as telephone communication lines. Baran’s group also ran a simplified computer simulation of such a network, using six nodes, which demonstrated its workability and survivability and indicated that the nodes did not need to store many message segments in order to be effective… A 1962 thesis by L. Kleinrock, then at Lincoln Laboratory, came to a similar conclusion.

With the important part coming after,

The Air Force did not follow up Baran’s work, apparently because of skepticism from the communications community, which felt that data hang-ups would be common and buffer storage requirements large. Baran’s work, apparently, was not well known to members of the DARPA community when they began their plans for computer communications networks.

Vint Cerf says as much in the youtube link provided above in the first section.

The work they are referring to is entitled “Recommendation to the air staff” by RAND, from August 1965. Quoting page 2

In our view it is possible to build a new large common-user communication network able to withstand heavy damage. Such a network can provide a major step forward in Air Force military communication capability.

and then page 40 for more lurid detail:

The cloud-of-doom attitude that nuclear war spells the end of the earth is slowly lifting from the minds of the many. … If war does not mean the end of the earth in a black and white manner, then it follows that we should do those things that make the shade of grey as light as possible: to plan now to minimize potential destruction and to do all those things necessary to permit the survivors of the holocaust to shuck their ashes and reconstruct the economy swiftly.

So this failed proposal in 1965 matches our claim by David Farber. They both worked at Rand. In a 2019 interview Farber stated

It allowed me to broaden out, quite a bit…. This is also the place where Paul Baran and I became good friends. We remained so for the rest of our lives.

This is consistent. In a 1988 interview he stated similarly:

He next joined RAND Corporation in Southern California where he was “heavily involved with, and affected” by, Paul Baran’s work.

So we have two possible strains, both sourcing back to early 1960s RAND work by Paul Baran; a connection between Baran and ARPAnet made by a good friend of his and an understandable scholarship mistake.

Living life in contemptuous bitterness and obscurity might be understandable but that’s not what Paul Baran did. He moved on and did many other great things. In March 2001, Wired interviewed him:

Wired: The myth of the Arpanet - which still persists - is that it was developed to withstand nuclear strikes. That’s wrong, isn’t it?

Paul Baran: Yes. Bob Taylor had a couple of computer terminals speaking to different machines, and his idea was to have some way of having a terminal speak to any of them and have a network. That’s really the origin of the Arpanet. The method used to connect things together was an open issue for a time.

But some contention remained. First, as a 2016 article in The Conversation points out, RAND in Santa Monica and the original ARPANET node at UCLA were a short bus ride away from each other.

Could be a coincidence. Baran is a little skeptical of it though. Going back to the Wired article:

Wired: Taylor heard about not through you, but through Donald Davies originally?

Baran: I have two different views on that. I didn’t pay much attention to it then, but with all the nonsense about it, I went back and started digging through the old records. I don’t believe anything unless I can find it in writing, in contemporaneous documentation. I had many, many discussions with the folks at Arpa, starting in the very early ’60s. The information about packet switching was not a surprise, not new. People can listen to things and put them in the back of their mind. So you don’t know. People say they’d never heard of me at the time, yet I’d chaired a session with them in it.

Here’s where we get our first potential conflict. The ARPA people say they didn’t know about or were influenced by Baran’s work yet Baran finds that implausible.

Really either could be true.

This was alluded to above. At one time there was a computing center with cubby holes. You’d place your program in a cubby-hole and then the machine operator would eventually feed it in, generate output, and you’d come back later to see the results.

There’s all kinds of problems with this. You aren’t actually touching the computer. Syntax errors would have the turnaround time of days to correct. You had to go, physically, to the machine.

The fix here was time-sharing; the ability of the computer to multi-task. This meant multiple people could interact with one computer simultaneously.

In order to do that you needed multiple input terminals. It wasn’t long before people realized it’d be nice to be able to roll their terminal home with them and just call it in.

This led to remote terminals.

Then people realized they could call up any computer once it got a phone number if only they had some agreed way to talk to it. This is still 1960s.

So you had terminals talking to computers. Surely this will be followed up by computers talking to computers. That’s an obvious next step.

The point is that Paul Baran wasn’t chartering a path through the wilderness; networked time-sharing and resource combination was the clear trajectory. The obvious way to achieve this was to time-share the communication channel as well. That’s where you get packets and switching.

Or hey, there’s probably more to it. There always is.